Page created on September 12, 2018. Last updated on December 18, 2024 at 16:56

The postmortal changes can be divided into two: the early postmortal changes and the late. There are 5 early changes and 6 late.

Early postmortal changes:

- Pallor mortis (paleness)

- Occurs because the absence of the circulation, which causes blood to pool in the deepest part of the body

- Algor mortis (coldness)

- Around 6 hours after the death, the corpse gets cooled to the temperature of the surroundings

- Rigor mortis (stiffness)

- Right after death, the muscles relax. After 2-4 hours and until 24 hours after death, the muscles gradually become stiff. This happens because of the formation of irreversible actinomyosin complexes. The rigor mortis follows the Nysten-rule, which states that is begins at the muscles of the head and neck, and then the trunk muscles, then the upper then lastly the lower extremities. Rigor mortis resolves 72 hours after death, and resolution also follows the Nysten-rule.

- Cruor postmortalis (postmortal blood clot formation)

- Blood coagulates and forms clots 3-4 hours after death. This type of clot is yellow on the top and red on the bottom. The top part contains fibrin and serum and no cells, while the bottom part contains RBCs. The whole clot has a smooth surface, is shiny, wet and elastic. It doesn’t adhere (stick) to the vessel wall.

- A thrombus (a pre-mortal blood clot) has different characteristics and must be differentiated from the postmortal clot. A thrombus is matte, brittle, dry and attaches to the wall of the vessel.

- The postmortal clot can have different colors in some cases. It is yellow-green in jaundice, white in leukaemia, brownish in sepsis or muschroom poisoning. In the case of suffocation, the blood doesn’t clot at all.

- Livores mortuales (postmortal spots/patches)

- The hypostatic type of postmortal spots form in the deep parts of the body, like the back of the lungs, and in parts of skin that are not exposed to pressure (so not on the butt or the scapulae). They’re bluish-reddish and are caused by blood sitting still in vessels. They disappear when pressed.

- The imbibition type of postmortal spots appear along the superficial skin veins and are cause by haemoglobin leaking out of the vessels and into the surrounding tissues. Therefore, these spots don’t disappear under pressure.

- Postmortal spots must be differentiated from hematomas. The postmortal spots can be washed out with water, whereas hematomas cannot be. Histology can confirm the presence of a hematoma.

Late postmortal changes:

- Postmortal exsiccation

- If the eyes are open, the cornea and sclera will dry out and lose their transparency. Other wet organs will also dry out if they are in contact with air, for example the pericardium or pleura in case of a perforation.

- Maceration

- Epithelial surface that are in contact with fluids (like bladder, renal pelvis, skin) will shed off and dissolve into the fluid they are in contact with. This opaque fluid needs to be distinguished from pus. In the case of intrauterine death will the skin of the fetus shed off, like snake skin.

- Automalacia (postmortal autodigestion, autolysis)

- Many compartments in the body contain enzymes that will break down and digest tissues after death, like the stomach, pancreas and intestines. The stomach wall will be thinned out and may even be perforated, so the stomach acid can digest other organs in the abdominal cavity as well.

- The esophagus and airways may also be digested by stomach acid, as the acid can reflux from the stomach. The pancreatic enzymes can also digest the pancreas itself.

- Postmortal decomposition (putredo, heterolysis)

- In putredo, enzymes of aerob and anaerob bacteria present in the body will digest the tissues.

- This can cause pseudomelanosis and postmortal gas formation. You can read more about this on [postmortal emphysema of the liver]

- Mummification

- This only happens under specific circumstances, where the temperature is above 45°C and the air is dry. This blocks the bacterial proliferation, which stops the postmortal decomposition. Instead, the body loses water, dries out, becomes blackish-brown and parchment-like.

- Adipocere (grave wax, lipocere)

- The formation of adipocere requires moisture and soil rich in earth metals, or cold acidic water. This causes the fat in the body to split into glycerin and free fatty acids. The fatty acids then react with the earth metals to form a waxy, soap-like material.

Cell injury and cell death

Many things can injure cells. To understand the ways cells can adapt to injury, we must know a few terms.

- Hyperplasia is when cells divide, and the number of cells increase so the tissue increases in size. This happens after pregnancy, when the breast tissue cells proliferate to prepare for breast feeding.

- Hypertrophy is when the cells become larger, so the number of cells stay the same, but the tissue increases in size anyway. This happens when you work out your muscles, or when the heart muscle increases in size because the resistance in the vessels increases.

- Atrophy means when tissues and organs shrink, either because cells die or shrink or both. This is what occurs when muscles shrink after not being used.

- Metaplasia is when a certain type of tissue is replaced by another type of tissue that is not normally present there. This happens when the pseudostratified kinociliated columnar epithelium in the airways is replaced by squamous epithelium in response to long-term smoking.

The injurious stimuli and the cells responses are best summarized in a table.

| Type of injurious stimulus | Cellular response |

| Altered physiological stimuli, nonlethal injurious stimuli | Cellular adaptations |

|

Increased demand on cell, increased stimulation (by growth factors, hormones) |

Hyperplasia, hypertrophy |

|

Decreased nutrients, decreased stimulation |

Atrophy |

|

Chronic (long-term) irritation (physical, chemical) |

Metaplasia |

| Reduced oxygen supply, chemical injury, microbial infection | Cell injury |

|

Acute and transient (short-lasting) |

Acute reversible injury, cellular swelling, fatty change |

| Progressive and severe, long lasting, DNA damage | Cell death by apoptosis or necrosis |

| Metabolic alteration, genetic or acquired | Intracellular accumulation of compounds, calcification |

| Long-term, cumulative sublethal injury | Cellular aging, senescence. |

How cells can respond to different stimuli. Adaptation can mean metaplasia, atrophy, hyperplasia or hypertrophy.

How cells can respond to different stimuli. Adaptation can mean metaplasia, atrophy, hyperplasia or hypertrophy.

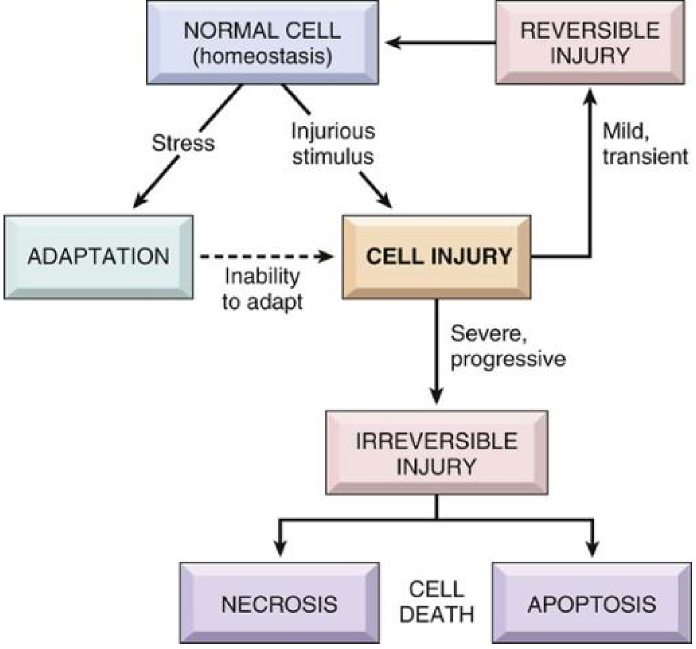

The figure to the right is often used to illustrate how a cell can respond to different stimuli. An “injurious stimulus” can be many things, but most commonly we talk about hypoxia or even anoxia. Hypoxia and anoxia usually come from ischemia, the word for decreased (either partial or total) blood perfusion. Ischemia often occurs because the arterial blood supply to a tissue is blocked, the level of blood in the body is low (anemia) or that the blood is not well enough oxygenated.

No matter what the cause of the ischemia is, the outcome for the cell is the same. Almost every cell needs oxygen to drive the oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria to supply the cell with ATP. When oxygen is limited, ATP supply becomes limited, which causes the cell to respond in three ways:

- The ion pumps that uphold the concentration of certain ions in the cell, and therefore make sure the cell is isotonic, need ATP and start failing. This causes Ca2+, Na+ and water to flow into the cell, and K+ to flow out. This causes the cell to swell.

- The cell switches from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism, which means that glycolysis is upregulated. Glycolysis doesn’t produce as much ATP as oxidative phosphorylation, and it also produces lactic acid. Lactic acid lowers the pH of the cell, which makes the chromatin in the nucleus clump together.

- Ribosomes start failing, which decreases protein synthesis and therefore causes deposition of lipids in the cell.

Other causes of cell injury

- Physical agents, like physical trauma, extreme temperature of atmospheric pressure, radiation, electric shock

- Chemical agents, like hypertonic solutions and poisons

- Environmental factors, like pesticides, CO, asbestos, alcohol and drugs

- Infectious agents, like viruses, bacteria, fungi or parasites

- Immunological reactions, like immune reactions against infected cells or autoimmune reactions against healthy cells

- Genetic abnormalities, like Down syndrome, enzyme defects or accumulation of damaged DNA

- Nutritional problems, like protein or vitamin deficiencies, or even an excess of nutrition

The two main types of cell death

You’ve definitely heard of these before, but it’s time to sum up the differences and go into detail on them.

| Property | Apoptosis | Necrosis |

| Physiological or pathological | Can be both | Always pathological |

| Causes inflammation | No | Yes |

| Requires ATP | Yes | No |

| Effects | Mostly good, sometimes bad | Always bad |

| Cell size | Shrinking | Swelling |

Necrosis is detailed in topic 3, while apoptosis is detailed in topic 7.