Table of Contents

Page created on April 17, 2022. Last updated on December 18, 2024 at 16:58

Ileus

Introduction and epidemiology

Ileus refers to the inability of intestinal contents to pass through the intestinal tract. We can distinguish multiple types according to the pathomechanism:

- Mechanical ileus – due to a mechanical obstruction of the bowels

- Obstructive ileus

- Bowel strangulation

- Dynamic ileus – due to functional impairment of peristalsis

- Paralytic ileus

- Spastic ileus

Obstructive ileus may be further classified as small bowel obstruction (SBO), large bowel obstruction, and gastric outlet obstruction. Mechanical ileus is an emergency as it may lead to strangulation, bowel perforation, and sepsis.

Because spastic ileus is so rare, most authors divide ileus into mechanical and paralytic types, ignoring spastic ileus completely.

Etiology and types

Obstructive ileus is the most common type. Obstruction may occur in the small bowel or large bowel. It may be caused by:

- Luminal obstruction from the inside

- Faecal impaction

- Gallstone

- Foreign body

- Parasites

- Certain foods (grapes, orange)

- Bowel wall lesion

- Strictures

- Due to inflammation (due to Crohn disease, etc.)

- Due to irradiation

- Cancer

- Polyp

- Strictures

- Compression from the outside

- Herniation

- Adhesions

Adhesions are pathological fibrous strands of connective tissue between organs and tissues that are usually not connected. This is a common complication of abdominal surgery.

Bowel strangulation refers to the condition when the bowel is “strangulated”, which cuts of the blood supply of the affected bowel segment. This can occur due to bowel incarceration, volvulus, or intussusception. Bowel incarceration is a complication of hernia (topic B4). Volvulus refers to when a loop of bowel twists around the mesentery that supports it. Intussusception occurs when a segment of bowel folds into itself like a telescope. See the image here.

Paralytic ileus refers to ileus due to paralysis of the bowel wall muscles which drive peristalsis. This can occur due to a variety of reasons, most commonly due to:

- Hypokalaemia and other electrolyte disturbances

- Diabetes mellitus

- Peritonitis

- Abdominal surgery (postoperative ileus)

- Anticholinergic or opioid drugs

Postoperative (paralytic) ileus is common and physiologic. It typically resolves spontaneously within 72 hours.

Spastic ileus refers to ileus due to spasm of bowel wall muscles. This is very rare, but may occur due to porphyria, uraemia, or heavy metal poisoning.

Clinical features

Patients may present acutely with colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal distension, and lack of passage of faeces and gas. Vomit may contain bile or faeces. Patients with ileus often develop hypovolaemia (due to vomiting and third-spacing of fluid).

Findings on auscultation are characteristic and important in forming a suspicion of ileus. They depend on the stage of development (early/late) and type of ileus.

|

|

Early phase |

Late phase |

|

Mechanical ileus |

High-pitched, metallic-like bowel sounds |

Absent bowel sounds |

|

Dynamic ileus |

Decreased bowel sounds |

Absent bowel sounds |

Complicated ileus occurs if bowel is necrotic or perforated, in which case the patient may be very ill (septic) and peritonitic.

Diagnosis and evaluation

Patients should be evaluated for herniation and trauma. Digital rectal examination should be performed, as the rectum will be tight (collapsed) in case of mechanical ileus and loose in case of paralytic ileus. Blood per DRE may be a sign of strangulation or cancer.

Abdominal x-ray or CT should be performed and may show characteristic air-fluid levels in the bowels, bowel dilation proximal to the obstruction, and sometimes the point of mechanical obstruction itself.

Treatment

Ileus should always be treated inpatient. The initial intervention is stabilisation. IV fluids are often necessary due to hypovolaemia, and any electrolyte disturbances should be treated. A nasogastric tube may be used to decompress the bowels. Prophylactic antibiotics should be used for complicated ileus.

Mechanical ileus requires surgery or endoscopy to treat the underlying cause. Complicated mechanical ileus requires emergency surgery, while uncomplicated ileus may only require timely surgery.

Dynamic ileus is not treated with surgery; instead, the underlying cause should be treated.

Complications

- Bowel necrosis

- Bowel perforation

- Peritonitis

- Hypovolaemic shock

- Sepsis

Peritonitis

Introduction and epidemiology

Peritonitis is the inflammation of the peritoneum, which lines the abdominal wall and most abdominal organs. We distinguish primary peritonitis (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis) and secondary peritonitis. Secondary peritonitis is peritonitis caused by bacterial infection from a surgically treatable intraabdominal source, like GI perforation, appendicitis, trauma, etc. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is peritonitis caused by bacterial infection of ascitic fluid which occurs in the absence of any surgically treatable intraabdominal source. The secondary form is much more common.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is usually a monomicrobial infection, while secondary peritonitis is usually a polymicrobial infection. Secondary peritonitis may be generalised or local, while primary peritonitis is always generalised.

Peritonitis is a severe condition as it has a high risk of progressing to sepsis with high mortality. The underlying cause must be sought and treated.

Etiology

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a disease of cirrhotic patients, as it almost exclusively occurs in patients with ascites due to cirrhosis, and not ascites due to other causes. The pathomechanism is not well known but involves bacterial translocation from the intestinal lumen to lymph nodes, from which the bacteria spread to the circulation, eventually colonising the ascitic fluid.

Secondary peritonitis occurs due to:

- Perforation of an abdominal organ

- Perforated duodenal ulcer

- Perforated appendicitis

- Perforated diverticulitis

- Mesenteric ischaemia

- Abdominal organ inflammation with spread to adjacent peritoneum

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulitis

- Pancreatitis

- Penetrating wounds to the abdomen

- Surgery

- Leakage of intestinal anastomosis

Clinical features

Peritonitis causes abdominal pain. Movement usually worsens the pain, causing the patient to lie completely still, usually with the knees bent. Even gentle percussion over the affected area of the abdomen causes pain. “Guarding” on palpation, as well as rebound tenderness, are typical signs of peritonitis. The heel-drop test may be positive. See also topic A25 of surgery for the physical signs of peritonitis.

If generalised, peritonitis also causes signs of infection like fever.

Peritonitic signs in only one quadrant means local peritonitis is probable, while diffuse peritonitic signs is suspicious for generalised peritonitis.

Diagnosis and evaluation

The presence of peritonitis is usually established by physical examination, but the underlying cause must be sought. Stable patients should undergo imaging (x-ray, CT, ultrasonography) to identify the underlying cause. However, unstable or very ill-appearing patients may skip imaging to avoid delaying surgery.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is diagnosed if the patient has cirrhosis and no surgically treatable intraabdominal source. Neutrophil count of > 250/µL in the ascitic fluid supports the diagnosis.

The treatment of secondary peritonitis involves supportive therapy, empiric wide-spectrum antibiotics, and treatment of the underlying cause, which almost always requires surgery. Local peritonitis does not invariably require antibiotics, for example when caused by appendicitis.

The treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis involves fluid resuscitation and empiric antibiotics, without surgery.

Acute abdomen

Introduction

Acute abdomen refers to acute onset abdominal pain. There’s a large number of conditions which can cause acute abdomen, and so knowing the differential diagnosis and investigations to distinguish them is important. The presence of typical risk factors, gender, and age for a specific cause can also help the diagnosis, and so knowing these is important as well. It’s important to remember that atypical presentations exist, of course.

Life-threatening conditions

It’s important to recognise or exclude life-threatening conditions, including AAA rupture, mesenteric ischaemia, GI perforation, ectopic pregnancy, etc.

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture |

Elderly male patient with cardiovascular risk factors, especially hypertension or known AAA |

Triad of severe acute abdominal pain, pulsatile abdominal mass, haemodynamic instability |

|

Mesenteric ischaemia |

Elderly patient with cardiovascular risk factors or atrial fibrillation |

“Pain out of proportion to the physical examination” (severe pain but normal physical examination), often peritonitic |

|

Gastrointestinal perforation |

Elderly patient with known ulcer or GI disease, recent abdominal surgery |

Severe, diffuse abdominal pain, often peritonitic |

|

Acute bowel obstruction |

Patient with recent abdominal surgery or known hernia |

Abdominal distension, vomiting, absence of flatus |

|

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

Any female of childbearing age |

Amenorrhoea, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, positive hCG |

|

(Inferior) Myocardial infarction |

Older patient with diabetes |

Epigastric pain |

|

Aortic dissection |

Elderly male patient with cardiovascular risk factors, especially hypertension |

Tearing/ripping pain, associated symptoms of downstream ischaemia |

Differential diagnosis by location

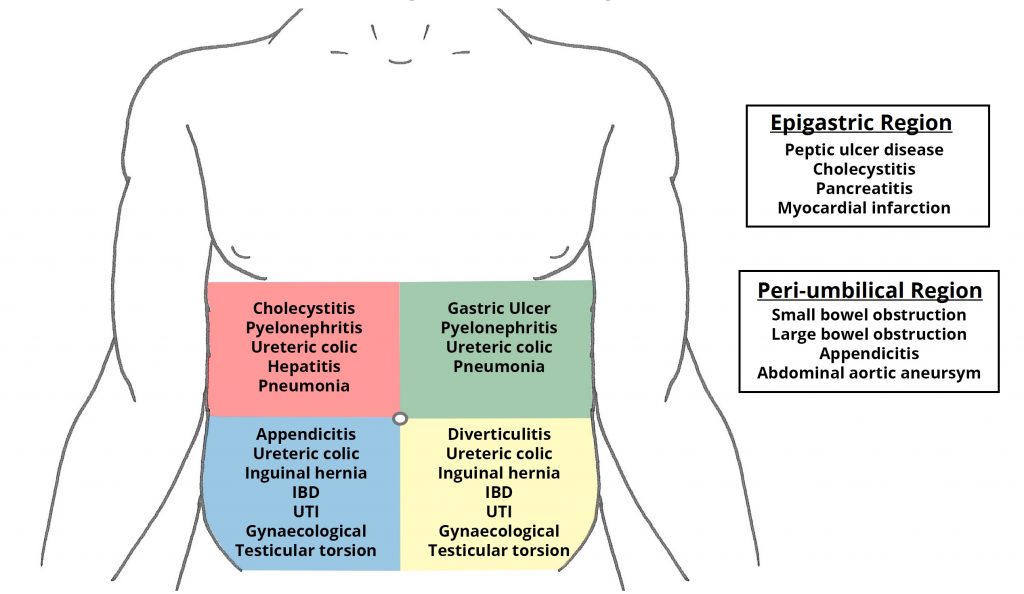

Different causes of acute abdomen cause pain in certain typical areas. This image shows the most common.

Some of the differential diagnoses for pain felt in the different regions of the abdomen. From https://teachmesurgery.com/general/presentations/acute-abdomen/

Right upper quadrant (RUQ)

The right upper quadrant is home to the liver and biliary system, and therefore also home to most cases of pain caused by hepatic and biliary disorders.

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Cholecystitis |

Patient with the 6 Fs |

Steady, severe RUQ or epigastric pain, positive Murphy sign |

|

Cholelithiasis |

Patient with the 6 Fs |

Intense, dull, constant RUQ or epigastric discomfort, sweating, nausea, vomiting |

|

Cholangitis |

Patient with the 6 Fs |

Charcot’s triad of fever, RUQ abdominal pain, jaundice |

|

Acute pancreatitis |

Patient with alcoholism, 6Fs, known hypertriglyceridaemia |

RUQ or epigastric pain, band-like radiation to the back, nausea, vomiting |

|

Hepatitis |

IV drug user, paracetamol intoxication, recent travel abroad |

RUQ pain, liver tenderness |

|

Lower lobe pneumonia |

– |

Basal crepitations, coughing, dyspnoea |

Epigastrium

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Peptic ulcer disease/gastritis |

Smoking, NSAID use, known H. pylori |

Epigastric/LUQ pain, indigestion, reflux symptoms |

|

Acute pancreatitis |

Patient with alcoholism, 6Fs, known hypertriglyceridaemia |

RUQ or epigastric pain, band-like radiation to the back, nausea, vomiting |

|

Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture |

Elderly male patient with cardiovascular risk factors, especially hypertension or known AAA |

Triad of severe acute abdominal pain, pulsatile abdominal mass, haemodynamic instability |

|

Lower lobe pneumonia |

– |

Basal crepitations, coughing, dyspnoea |

Left upper quadrant (LUQ)

The left upper quadrant is home to the spleen, pancreas, and stomach.

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Peptic ulcer disease/gastritis |

Smoking, NSAID use, known H. pylori |

Epigastric/LUQ pain, indigestion, reflux symptoms |

|

Splenic infarct/rupture |

– |

Tender/enlarged spleen |

|

Lower lobe pneumonia |

– |

Basal crepitations, coughing, dyspnoea |

Right lower quadrant (RLQ)

The right lower quadrant is home to the appendix, terminal ileum, as well as the ovary, fallopian tube, and referred pain from the testis.

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Acute appendicitis |

Young adult, previously healthy |

Pain originating periumbilically, later migrating to the McBurney point. Tenderness. Positive Rovsing, psoas, or obturator sign. |

|

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Young adult, known history of GI complaints |

Local peritonitis |

|

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

Any female of childbearing age |

Amenorrhoea, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, positive hCG |

|

Ovarian torsion |

Known ovarian cyst or tumour |

Unilateral lower abdominal or pelvic pain, nausea/vomiting, palpable adnexal mass |

|

Testicular torsion |

Young male (teenager) |

Testicular and lower abdominal pain, swollen and tender testis |

Left lower quadrant (LLQ)

The left lower quadrant is home to the part of the colon most frequently affected by diverticulitis, as well as the ovary, fallopian tube, and referred pain from the testis.

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Diverticulitis |

Elderly patient |

Low-grade fever, nausea/vomiting, recent change in bowel habits |

|

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

Any female of childbearing age |

Amenorrhoea, abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, positive hCG |

|

Ovarian torsion |

Known ovarian cyst or tumour |

Unilateral lower abdominal or pelvic pain, nausea/vomiting, palpable adnexal mass |

|

Testicular torsion |

Young male (teenager) |

Testicular and lower abdominal pain, swollen and tender testis |

Diffuse abdominal pain

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Diabetic ketoacidosis |

Young patient without known T1D, or patient with known T1D and poor compliance, recent stress/infection |

Polyuria, neurological symptoms, dehydration, fruity odour, Kussmaul breathing |

|

Porphyria attack |

Known porphyria, recent drug change or infection |

Brown or reddish urine |

|

Mesenteric ischaemia |

Elderly patient with cardiovascular risk factors or atrial fibrillation |

“Pain out of proportion to the physical examination” (severe pain but normal physical examination), often peritonitic |

|

Acute bowel obstruction |

Patient with recent abdominal surgery or known hernia |

Abdominal distension, vomiting, absence of flatus |

Any quadrant

|

Disorder |

Typical patient |

Typical findings |

|

Ureteric colic/nephrolithiasis |

History of stone disease |

Colicky pain, flank pain, haematuria |

|

Pyelonephritis |

Women, pregnancy, known urinary tract obstruction |

Tender costovertebral angle on percussion, fever, chills, UVI symptoms |

Initial management

Routine investigations

Initial management involves performing routine investigations, including blood test (WBCs, CRP, Hb, amylase, liver function tests, electrolytes), obtaining IV access and providing fluids if necessary, and analgesia.

To exclude ectopic pregnancy and atypical presentation of myocardial infarction, serum hCG should be measured in all females of childbearing age and an ECG should be obtained in all patients, or at least the elderly ones.

Analgesia

Many are afraid of giving strong analgesics which may mask physical examination findings and interfere with the diagnosis, but multiple high-quality studies (RCTs) have disproved this (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Therefore, there’s no good reason patients shouldn’t be relieved of their pain, usually with strong analgesics like morphine.

History and physical examination

The patient’s history and physical examination should be taken. Characterisation of the timing and features of the pain is especially important. It’s important to recognise features suggestive of severe disease, like severe, opioid-refractory pain, haemodynamic instability, sudden onset pain, and signs of peritonitis. Care should be made in elderly, where typical signs of the specific diseases may be absent, and severe disease may present without findings of severe disease.