Table of Contents

Page created on September 23, 2018. Last updated on December 18, 2024 at 16:56

Degeneration

Degeneration is a form of deterioration. It can be explained as the change of a tissue to a lower or less functionally active form.

Degeneration is sublethal injuries to the cells. It doesn’t kill the tissue, but the tissue will have some damages or flaws that can make it less functional. Many of them are related to aging and genetics and can get worse by a poor lifestyle and eating habits.

There are many types of degeneration, and all of them are characterized by accumulation of something inside the cell. For example: Parenchymal degeneration has water accumulation and fatty degeneration has fat accumulation.

Let’s take a closer look at the different types of degeneration.

Parenchymal degeneration

Parenchymal degeneration can be seen in light microscopy as hydropic degeneration or cellular swellings, and its reversible.

The reason behind why it’s called cellular swelling is because the cells loses their capability of maintaining ionic and fluid homeostasis due to reduced oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. This will lead to depletion of ATP, which is needed to fuel the Na+/K+ ATPase. Water will therefore flow into the cell.

When it affects many cells, it causes some pallor and increases turgor (makes it firmer) and the weight of the organ.

In the microscope you can see small clear vacuoles within the cytoplasm. These represent pinched off segments of the ER. See slide 7 for what parenchymal degeneration of the kidney looks like.

Fatty degeneration

Fatty degeneration is the abnormal accumulation of triglycerides within parenchymal cells. It’s often seen in cells participating in fat metabolism, like in liver, heart, muscle and kidney. It’s also called steatosis.

The causes of fatty degeneration include:

- Toxins

- Protein malnutrition

- Diabetes mellitus

- Obesity

- Anoxia

- Alcohol abuse

The most common causes in developed nations are alcohol abuse and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease due to diabetes and obesity.

The liver steatosis can result from these factors:

- Exposure to alcohol, dysfunction of mitochondrial and cellular membranes, hypoxia and oxidative stress.

- Impaired assembly and secretion of lipoproteins lead to steatosis.

- Increased peripheral catabolism of fat

When you drink alcohol, NADH will accumulate and NAD+ will be depleted, and this will result in an increased lipid synthesis. Daily intake of 80g (six beers) alcohol generate a significant risk for severe hepatic injury. However, short term ingestion of e.g. six beers generally produces a mild reversible hepatic steatosis. Alcohol is dangerous y’all!

Morphology of fatty degeneration

Macroscopically, the fatty liver of chronic alcoholism is large, can weight up to 4-6 kg and looks yellow and greasy. This increase in weight of the liver is called hepatomegaly.

Some fibrous tissue may also develop around the terminal hepatic veins and extend into the adjacent sinusoids with heavy alcohol abuse. This liver fibrosis is called hepatic cirrhosis.

Also, in the beginning, the fat will accumulate in only some parts of the liver (centrolobular or peripherolobular) but becomes panlobular with prolonged alcohol consumption.

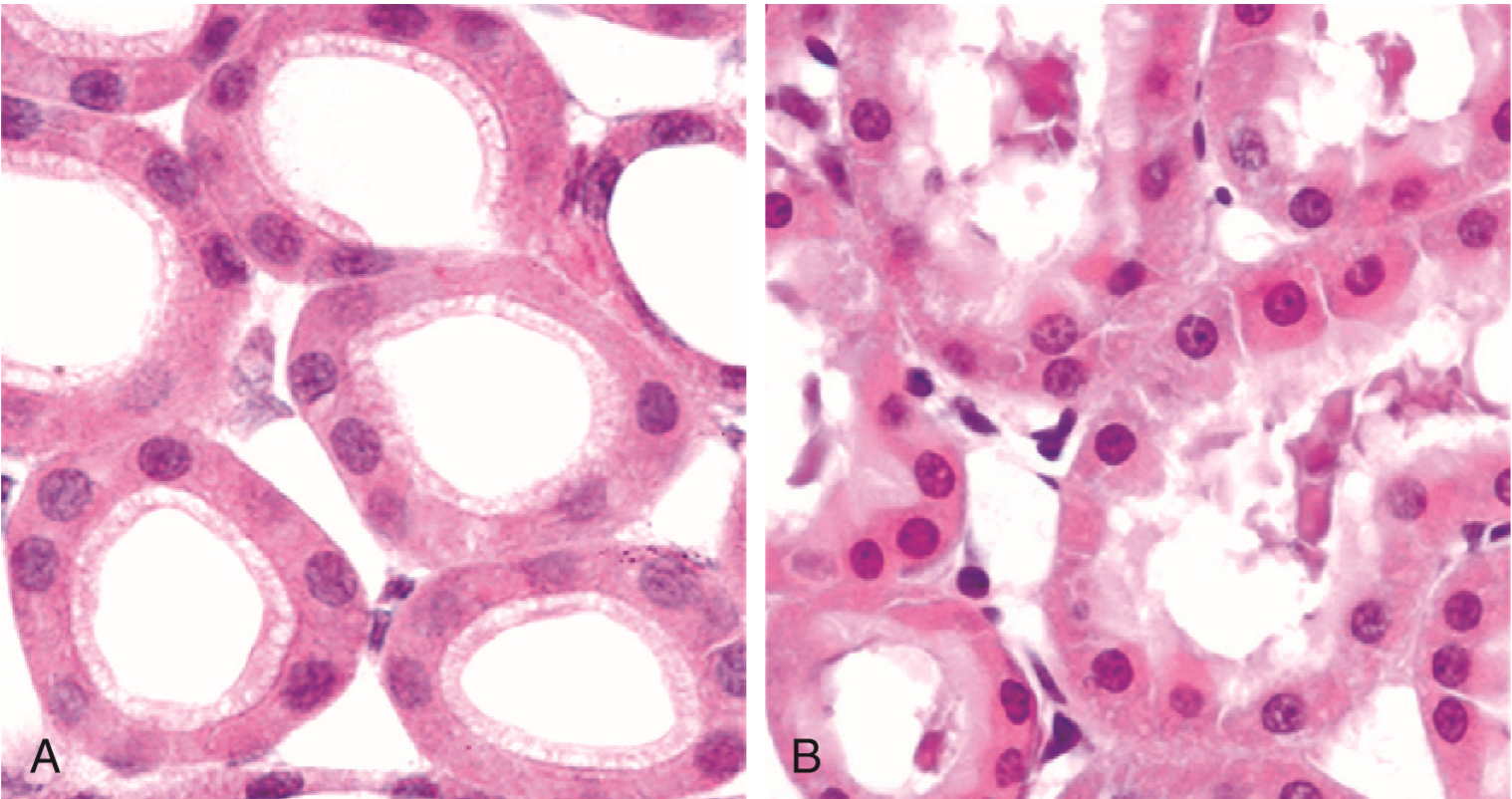

Microscopically, microvesicular lipid droplets may be seen in hepatocytes in moderate alcohol intake. If there’s chronic alcohol abuse, clear macrovesicular globules are present, and they will compress the nucleus of the hepatocytes and eventually displace it to the periphery of the cell. You can see how it looks in slide 8.

Total alcohol withdrawal and a special diet is considered sufficient treatment for fatty degeneration, as its reversible.

Fatty degeneration in other organs

Steatosis may happen in the heart, often due to poor oxygenation. The fat is distributed away from the vessels and produces a “tiger-striped heart”.

Accumulation of fat in phagocytic cells is also possible. The fat is usually made up from cholesterol esters.

In atherosceloris, smooth muscle cells and macrophages within tunica intima of aorta and big arteries are filled with lipid vacuoles. Most of the lipid vacuoles are made up of cholesterol and cholesteryl esters.